Study: Microbial Life Helps Warming Ocean Adapt

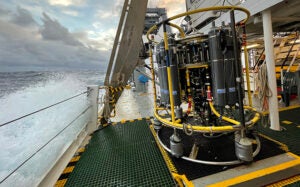

Three BIOS researchers were among the authors of a paper on microbial life and climate change published this month in the journal Nature Communications. BIOS faculty members Nicholas Bates and Rod Johnson, along with BIOS adjunct faculty member Mike Lomas of the Bigelow Laboratory in Maine, looked at three decades of data collected at the BIOS Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study site in the Sargasso Sea on board research vessel Atlantic Explorer. Photo by Yuuki Niimi

Climate change will challenge many of the processes that sustain life around the globe, but new research led by Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences provides a fresh look at the planet’s resiliency. The results reveal how microscopic ocean life that drives the carbon cycle in the Atlantic is adapting to warmer conditions. The news does not mean the end of the planet’s concerns, but it can help researchers better forecast the future.

The study, published in Nature Communications, examined 30 years of data from the Sargasso Sea and found that biological systems that regulate carbon maintained vital processes despite the effects of climate change. This suggests that the surface ocean may adapt better to climate change than current scientific models take into account.

“We often view the response of ocean carbon cycling to global warming as an on-off switch, but these results show it’s a dimmer switch and has some flexibility to take care of itself,” said lead author on the study Mike Lomas, who is involved with several projects at BIOS in addition to his role as a Bigelow Laboratory Senior Research Scientist. “It will reach its limits though, and we shouldn’t use these results as an escape clause for the consequences of our actions.”

Carbon fuels all life and ecosystems throughout the water column as it gets pumped from the surface to deeper waters. Phytoplankton are one of the primary vehicles for this carbon sequestration and transport. However, climate change puts them, and the process, at risk.

Phytoplankton live in surface waters, but they rely on nutrients from the deep ocean. These nutrients rise through layers of water that are separated like a cake. However, the boundaries between the layers become more defined as the ocean warms. This makes it harder for the nutrients to reach phytoplankton, which could reduce their populations and stop the biological process that sequesters carbon and sends it to the deep ocean.

“Except our research revealed that the microscopic life in the ocean responds, takes up carbon dioxide, and continues to function even when there are few nutrients,” Lomas said.

The new study examined key metrics like carbon production and cycling, phytoplankton activity, and nutrient availability in the same area from 1990-2020. Results showed that carbon export was maintained as phytoplankton populations declined because other small organisms that graze on them took up the slack. Ecosystems also adapted by becoming more efficient and using less nutrients to export carbon.

These results provide insights into how ocean ecosystems respond to climate change – and to the methods scientists use to study them. They highlight the importance of research to replace estimates with more nuanced understanding of nature’s complexity.

“The success of this research points out the need for these kinds of long-term studies,” Lomas said. “How far can we push phytoplankton before they give up the ghost and truly stop fixing carbon? Understanding how these processes continue to work in the face of climate challenges, and where they will fail, is vital to predicting and preparing for the effects of climate change.”

“This new finding about how ocean biology impacts the ocean carbon cycle owes much to the efforts and dedication of many scientists working on this study over the past thirty years,” added Professor Nick Bates, senior scientist and director of research at BIOS.

Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences is an independent, nonprofit research institute located in East Boothbay, Maine. From the Arctic to the Antarctic, Bigelow Laboratory scientists use innovative approaches to study the foundation of global ocean health and unlock its potential to improve the future for all life on the planet. Learn more at bigelow.org, and join the conversation on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.